Licensed to drill

Energy Security has become one of the most hotly debated political issues of 2015. The new Conservative government has made its support for onshore oil and gas drilling, both conventional and hydraulic fracturing, abundantly clear. Tim Pugh explains what the industry can expect from recent legal and political developments

This article concentrates on fracking. Onshore extraction by conventional means continues in its existing strongholds almost unnoticed and largely untainted by US images of blowtorch water taps and environmental dereliction.

Government spokespeople have determinedly maintained progress following the recently passed Infrastructure Act. Moratoria in Scotland, Wales and, most recently, Northern Ireland may seemingly have changed industry’s landscape for the worse but seasoned observers view this, as vote-catching in advance of devolved government elections in 2016. Post elections and devolution of energy powers, evidence from already commissioned investigations, seems likely to endorse arguments that fracking can proceed safely.

PEDLs

In commercial terms, the most significant development has been the long awaited award of licences as part of the 14th Onshore Licensing Round. On 18th August, some 27 licenses were granted, with a further 132 blocks ready to be licensed subject to Habitats Regulations Assessments being completed satisfactorily. A recent consultation paper stands to ease the path even in these highly protected areas.

Infrastructure Act 2015

In purely legal terms, the major development so far is, by far, the Infrastructure Act.

The Act includes rights for those holding onshore licences (PEDLs) to use “deep level land” (land below 300 metres below surface level) and sets out supplementary provisions concerning payment schemes, notices and safeguards. It paves the way both for removing private law obstacles and for meeting the most severe environmental concerns.

PEDL holders’ rights to use deep level land will include:

- drilling, boring, fracturing or otherwise altering it

- installing, keeping, using or removing infrastructure

- passing any substance through infrastructure within it

- putting, keeping and removing any substance into or from it

- leaving the land in a different condition and

- leaving any substance or infrastructure in it.

The purposes for which the rights may be used include:

- searching for petroleum or deep level thermal energy

- assessing the feasibility of exploiting it

- preparing for exploiting it and

- decommissioning and any other activity for the purpose of or in consequence of exploiting petroleum or geothermal energy

In a step designed simultaneously to calm householders and reduce risks of the courts granting injunctions, owners of land subject to exercise of deep level use rights by another would be absolved from tortious liability to others for loss or damage attributable to that exercise.

The price of securing Parliament’s consent to deep level rights was a plethora of commitments and qualifications. These were necessary to quell a back-bench rebellion within government, meet strong concerns voiced by the Environmental Audit Committee and calm the opposition in a frantic drive to force the Infrastructure Act before the 2015 General Election. Some were embedded in the Act, others were to follow in regulations to be passed by both Houses of Parliament.

The commitments and qualifications included:

- Prohibitions on the issue of well consents unless they include conditions

- Absolutely prohibiting hydraulic fracturing within 1000 metres of the surface

- Prohibiting hydraulic fracturing from taking place below 1000 metres without the Secretary of State’s consent

- Requiring a number of conditions to be met before the Secretary of State issues such a consent, including:

- environmental impacts having been taken into account by the local planning authority

- appropriate arrangements having been made for independent inspection of well integrity

- methane monitoring having been undertaken in the 12 months before hydraulic fracturing begins

- arrangements for monitoring methane emissions into the atmosphere

- cumulative effects of hydraulic fracturing proposals having been taken into account

- approval of substances to be used (or use of approved substances) in hydraulic fracturing

- imposition of a restoration condition having been considered by the local planning authority

- relevant water undertakers having been consulted

- notice having been given to the public of the application for planning permission

The list of conditions seems stringent and makes for reassuring speeches and newspaper copy. But in reality (and this is a strength of the UK regulatory system) they mostly do little more than reiterate a selected range of existing requirements. The majority are already integral to the process of securing planning permission, well consent and environmental permits for exploring for and exploiting onshore shale oil and gas reserves.

Notable ‘additions’ were also to have included prohibitions on hydraulic fracturing within ‘protected areas’ and ‘protected groundwater areas’. But the prohibitions, as they have emerged, are less prohibitive than first appeared likely.

July Regulations

Draft regulations were laid before Parliament in mid-July. They must be subject to positive resolutions of the Lords and the Commons before becoming law. The July draft regulations, define protected areas relatively narrowly – only National Parks, AONBs, the Norfolk Broads and World Heritage Sites – omitting SSSIs and European Protected Sites – and address protected groundwater. They define protected groundwater source areas to be within (a) 50 metres of a point at which water is abstracted for domestic or food production purposes or (b) within or above a zone 50 day groundwater travel time of such an abstraction point. Hydraulic fracturing (but not conventional drilling) would be prohibited above 1200 metres below the surface of such areas.

In a further development, in early November, the Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC) published its consultation paper on “Surface Development Restrictions for Hydraulic Fracturing”. The Consultation runs until 16 December. If the proposals are adopted they will form the latest piece in a complicated regulatory jigsaw.

November consultation

The November Consultation proposes that conditions within newly granted PEDLs (essentially those under the 14th Onshore Round and later grants) will forbid surface activity required for carrying out “associated hydraulic fracturing”. This is defined in the Infrastructure Act as something that (over and above drilling) would involve more than 1,000 cubic metres (40 per cent of an Olympic Swimming Pool) of fluid at each stage of the fracturing process or more than 10,000 cubic metres (four Olympic swimming pools) of fluid in total – in specified protected areas.

The protected areas for the purposes of the November Consultation include SSSIs and Habitats and Wild Birds Directive sites in addition to those that would be protected from fracking above 1200 metres below ground under the 2015 Regulations. Therefore an apparent loophole would be closed. Nevertheless, it would only be closed in relation to PEDLs yet to be granted. Those PEDLs already in place would notionally be free of the restriction.

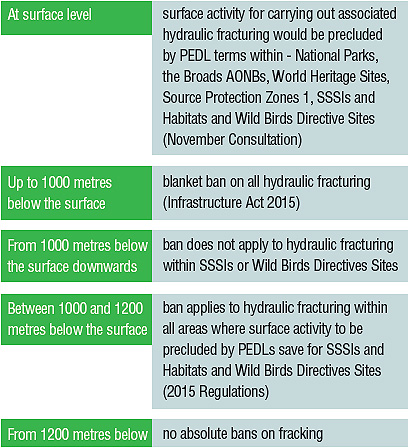

The interface between the various restrictions can be seen as follows.

Apart from surface restrictions, other than between 1000 metres and 1200 metres beneath the surface, there are few material differences between fracking under land generally and fracking beneath protected areas.

The main thing to take from the November Consultation, other than that the proposed restrictions will not apply to existing PEDLs under which current applications and appeals are to be determined, is that there are no new restrictions proposed for surface activities not required for “associated hydraulic fracking” as defined. They would not apply to conventional extraction techniques. Unusually, both industry representatives and the environmental lobby are likely to regard the Consultation as benign or positive.

From an industry perspective, the constraints under the November Consultation add little to those likely to apply anyway under planning policies and environmental permitting policy. Nevertheless, they will wish to ensure that the detail is not overly prescriptive and certainly no more so than the general propositions consulted upon.

From an environmental perspective, placing a blanket ban on surface activities within the full range of protected areas provides consistency with planning and environmental policy and should for future PEDLs obviate the likelihood of some of the least attractive surface activities applying within protected areas.

In Parliament, the process grinds on. The July Draft Regulations have yet to be passed by the House of Lords or the House of Commons. Debates are expected in the near future. Ministers were criticised on 15 September by the Lords Statutory Instruments Committee for not having consulted the public on the draft regulations or having made a Ministerial Statement about them. Whilst, debates in the Lords and Commons seem likely to replay some of the most controversial issues from before the Bill was enacted, the proposals in the November Consultation will ease the way.

Planning

Meanwhile, on the planning permission front, at the beginning of September, Greg Clark (DCLG) and Amber Rudd (DECC) issued a joint ministerial statement reinforcing Government support for onshore oil and gas development as a means of promoting national energy security and boosting the economy. Sixteen-week targets have been set for planning authorities determining onshore oil and gas applications, with special measures promised for serial under-performers. Fast track appeals and call-ins with ministerial determination have also been promised by Greg Clark.

In Lancashire, one of the homes of the Northern Power House, Cuadrilla’s proposals at Roseacre Wood and Little Plumpton on the Fylde Coast are at appeal and will test government mettle. Having been refused on narrow local grounds, in the face of overwhelmingly positive policy analysis, Greg Clark has now recovered both appeals for his own determination. With diminishing North Sea oil and gas revenues and desperation for new sources of energy security, the odds are on an early positive decision. In the meantime, conventional extraction proposals continue apace in the East Midlands with IGas’s proposals and in Surrey where conventional reserves in the Weald Basin look increasingly attractive.

To Conclude

The Government has pushed hard to resolve the main legal challenges to an onshore extraction programme in the UK. For the foreseeable future, Treasury has an absolute interest in ensuring that UK oil and gas can be extracted onshore and offshore efficiently and economically. Tax revenues and economic confidence flowing from oil and gas are vitally important.

Even so, wrinkles remain. In a densely populated country, with an active green protest lobby and many areas subject to designated landscape, groundwater, nature conservation or heritage protections, establishing a viable onshore oil industry will not be easy. It will remain particularly difficult for as long as oil prices remain low and costs of complying with tight regulatory controls stay high.

Nevertheless, although costly to meet, stringent environmental controls will remain essential. Without them, social licence for activities, which are poorly understood by the general public by companies few of which are well known, will simply not be achieved .Hearts and mind need to be won. This can only happen if the emerging industry delivers good-neighbour exemplar projects from the outset.

Berwin Leighton Paisner

Tim Pugh is Partner at law firm Berwin Leighton Paisner, an international law firm with 13 offices around the world including in the UK, Russia, Singapore, Hong Kong and United Arab Emirates amongst others. Over 50 Fortune 500 or FTSE 100 clients have relied on its legal advice to protect their interests.

For further information please visit: blplaw.com