Beneath the surface

DR ASSHETON CARTER HIGHLIGHTS THE IMPORTANCE OF ENGAGING THE FULL SUPPLY CHAIN IN THE DEBATE AROUND DEEP-SEA MINERAL EXTRACTION

In June 2021, the tiny Pacific Island nation of Nauru requested the International Seabed Authority to adopt deep-sea mineral exploitation regulation within two years, bringing to the fore the long running and highly controversial debate around this new industry.

By triggering the ‘two-year rule’ which allows for application of exploitation license after two years under whatever rules are in place at that time, the Government of Nauru has effectively given the ISA a deadline for completing talks on regulations governing deep-sea mining.

With so little still known about the long-term impact of deep-sea mining on marine ecosystems, there is strong opposition from environmental groups in particular, who are concerned that fast tracking regulations around mining will lead to a new rush on mineral rich sea beds.

But with the race to decarbonize gathering pace in the run up to this years’ crucial COP26 summit in November, can we afford to ignore this abundance of minerals that are so essential to the green energy transition?

Mining’s new frontier

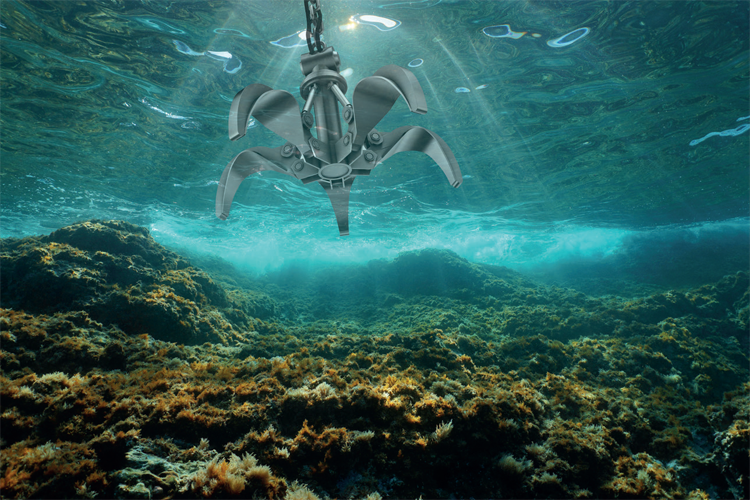

The objects of such controversy are the billions of tons of small rocks or polymetallic ‘nodules’ that lie on the seabed and are rich in minerals such as nickel, copper and cobalt We rely on these minerals in so many aspects of our lives, but particularly for batteries that power our electric vehicles and devices and renewable energy systems that will allow us to move away from burning fossil fuels.

One estimate suggests that there are 44 million tons of cobalt metal content alone in the Clarion Clipperton Zone, an area in the Pacific known to have large occurrences of nodules. Scientists and businesses have been researching and testing the viability of extraction and processing since the 1970s and considerable investment has been made into detailed studies in the last ten years.

Proponents of deep-sea mining argue its benefits in contrast to mining on land, which can be energy intensive, dotted with human rights issues and can encroach into forests of significant conservation value. They also highlight the opportunity to utilize mining activity and the financial support of developers to gather scientific knowledge and improve knowledge about the biodiversity of the deep-sea.

Opponents are concerned about introducing deep-sea mining as yet another activity that threatens the marine environment. The impact on deep-sea biodiversity and the ecosystem’s ability to recover from mining activity is yet to be understood. They also raised concerns of the current governance mechanisms and question if additional minerals will be needed with an increase in circular economy.

While there is already a significant amount of work being undertaken by major contractors such as The Metals Company, GSR of the Deme Group and UK Seabed Resources to assess the potential environmental impact of deep-sea mining, there are scientists that believe they are far from gaining a satisfactory understanding of the abyssal plains, including how deep-sea organisms may be affected by the plumes of sediment caused by mining machinery. This is why Google, BMW Volvo Group and Samsung SDI, have recently joined the call for a moratorium on deep-sea mining until effective protection of the marine environment can be clearly demonstrated and all alternatives are explored.

Focusing on engagement

Controversy around the sourcing and mining of raw materials is nothing new, but the current spotlight on ESG and responsible supply chains means that the debate around deep-sea mining has come at a time when there is greater interest in the issue than ever before. There is a deep polarization of opinions on whether the potential ESG impacts are acceptable when weighed against the potential benefits.

To find a positive way forward in this debate it will be critical to ask the question: what does it mean to mine responsibly and is it possible to extract deep-sea minerals responsibly? What can we learn from the experience of gold mining or copper extraction, for example, which have come under such scrutiny and have made significant moves towards operating in a more sustainable way?

At the heart of the solution is the need for collaboration between stakeholders along the entire supply chain.

As an industry, taking responsibility for the potential social and environmental impacts of mining does not mean simply eliminating sources from the supply chain, it’s about looking for ways to engage and inform all parties of potential benefits and negative impacts, from metal exchanges to downstream manufacturers, investors and civil society organizations, which represent the general public, and ensuring everyone has a voice.

Although deep-sea mining exploration has been ongoing for decades, for those metal exchanges and downstream manufacturers who may need to make the decision of using these metals or not, should they become commercially available, it is a brand-new topic they have only recently become aware of. The World Economic Forum has created the Deep-Sea Minerals Dialogue as an impartial space for these downstream discussion on responsible sourcing considerations. It’s vital that the entire supply chain and stakeholders take advantage of this rare opportunity to really understand and make the wisest decision possible on a potential future industry.

Creating a framework for dialogue

A large part of this dialogue should be focused on how to create a practical, achievable framework for decision making on if and under what conditions deep-sea extraction should go ahead and, if so, what could responsible production that can be accepted by many stakeholders look like. While contractors, the ISA and national regulators work on establishing regulations for extraction permits, many questions remain for potential investors and potential buyers of these minerals, including those within the energy sector, as to how to ensure they are following best practice in relation to ESG.

Only when there is a commonly accepted framework in place, backed by the entire supply chain, will we be able to have constructive discussions weighing the opportunities and risks of exploring deep-sea minerals, and develop a way forward that has factored in the perspectives of different stakeholders.

While its likely to still be several years before deep-sea mining can actually begin, for those working in the energy sector, now is the time to engage in this important discussion that will help shape the future of the industry, as well as our planet.

DR ASSHETON CARTER

Dr Assheton Carter is CEO of TDi Sustainability, a global consultancy that helps businesses the world over to be more sustainable. Along the length and breadth of the supply chain, from artisanal mine to multinational corporation, TDi applies expertise to build responsible supply chains that work for people, for business and for the planet.

For further information please visit: https://tdi-sustainability.com